A Shift in Space-Time: How to Find Your Pace in a Pandemic

- Katlyn Roberts

- Oct 23, 2020

- 11 min read

Updated: Apr 21, 2021

Why time flies when society comes undone.

This pandemic is shaking us to our foundations. It’s literally forcing us to reconsider both time and space.

We’re struggling to block out our time like we used to. We’re unsure if we’re spending it correctly. We can’t decide if it’s moving too fast or too slow. Wasn’t it just March? We’ve been inside forever.

The space between us is wider and yet we’re in constant contact with each other over Zoom, social media, etc. We’re trying to be there for each other, to stick together, but not physically.

If you’re feeling rattled right now, it makes total sense. These two concepts are key to our fundamental understanding of our world and yet we’ve taken them completely for granted.

Or maybe we’ve taken for granted that society already decided our relationships with time and space. We didn’t get much of a choice in the matter. Now that the Coronavirus has caused cracks to form in the status quo… doesn’t it make you want to peek inside and see what’s underneath?

I’m going to do three things with this article:

Delightfully explain some scientific concepts you may or may not have learned in school.

Give you some actionable steps to literally speed up or slow down time, whatever’s your prerogative.

Help you feel better about your own life pace and the way you interact with the world.

It’s a tall order, I know, but I’ve got all the time in the world and not a drop to spare, so let’s do this.

A few weeks ago, Human Parts featured my story in which I compared these pandemic times to Joseph Campbell’s Hero’s Journey.

I’ve always been the type of person who thinks in stories and metaphors, not science and abstractions. But I was sick with Covid-19 for a long time and something about that brush with my own mortality shifted something in me. I’ve been doing a lot of stuff lately that I never would have done before. Like waking up early to go for a run (WTF?) and studying physics. This quote I referenced in my Hero’s Journey article is what made me curious:

The Hero’s Journey is a recognition of a beautiful design, a set of principles that govern the conduct of life and the world of storytelling the way physics and chemistry govern the physical world. — Christopher Vogler

It occurred to me that my way of seeing the world may have been a bit… incomplete. I suddenly found myself with an insatiable urge to bring my foundational understanding of how the world works into balance. Almost like my emotional and spiritual tendencies were being pulled by some unseen force towards the more physical and mental side of things.

In his lecture on The Great Courses, The Physics of Time, Theoretical Physicist Sean Caroll explains the connection between time and space. He asks us to imagine two arrows:

The Arrow of Time Shoots out and away from the Big Bang → from past to present to future.

The Arrow of Space Shoots out and away from the Earth → at least from our human perspective.

The point is that each concept has a genesis; the Big Bang and the Earth are our two launching-off points. The Arrow of Time expands (’cause of entropy) and the Arrow of Space contracts (’cause of gravity).

I’m asking you to think in a super abstract way and if that’s tough for you, don’t worry. I wasn’t used to that either before I dove into all this. I have a degree in screenwriting, not physics or metaphysics. But admit it, most of what you know about physics comes from the movies anyway. Who better to explain?

Stephen Hawking: [introducing himself for the first time] Hello. Jane Hawking: Hello. Stephen Hawking: Science. Jane Hawking: Arts. What are you?… Stephen Hawking: Cosmologist, I’m a Cosmologist. Jane Hawking: What is that? Stephen Hawking: It is a kind of religion for intelligent atheists. — Scene from The Theory of Everything

The concept of time has been on my mind since long before the pandemic. Really, since I moved in with my 83-year-old grandma, who (and I say this in the most loving way) moves like the sloth from Zootopia.

It’s not her fault. She’s had multiple strokes. I often find myself watching her, fascinated, as she takes 5 whole minutes to put on a glove. The damage to her brain makes her completely unaware of how slow she’s going. Interacting with her can be frustrating, but in my better moments, I’m overcome with empathy. I understand how she must feel because, compared to my peers, I often feel slow myself.

While some people can write an article in a day or even an hour, my articles usually take one or two weeks. The one you’re reading now is no exception.

This makes working for clients difficult. I can either be upfront about the number of hours I’m likely to work on a project and risk them deciding to find someone quicker and cheaper, or I can play down how much time a piece is actually going to take, accept the average pay based on the average time, and work multiple unpaid hours for the sake of getting hired in the first place.

Those that are most slow in making a promise are the most faithful in the performance of it. — Jean-Jacques Rousseau, one of the founders of Contractarianism

In our current social paradigm, my slow pace is an indication that I’m not as evolved as my peers, not as practiced. The expectation is that if I work hard enough, my pace will increase. But I’ve been writing every single day of my life since I was 11 years old. That’s almost 20 years of experience. How much more practiced should a 30-year-old, college-educated professional be? 20 years ago, Psychologist Richard Weisman started a long-term study to record pace-indicating factors like walking speed, people’s likeliness to help others, and coronary disease in cities like London, Madrid, Singapore, and New York. He found that our overall pace of life since then has increased by up to 30%.

That’s 30% in 20 years.

That’s jarring. Even if my Nana hadn’t had all those strokes, imagine how much the pace of life must have increased in her 83 years.

If we don’t use this pandemic to step back and consider not only how we’re spending our time, but how we value our time, just think what the expectations on us will be 20 years from now…

So how is it possible for different people to perceive time differently if we all have synchronized clocks? In The Physics of Time, Dr. Sean Caroll explains the three biological tenants of time perception:

1. Pulses Not only do our hearts and lungs serve as sort of internal pendulums (which are obviously subject to tempo changes), but the neurons in our brains keep track of time by traveling via rhythmic pulses as well (also subject to tempo changes).

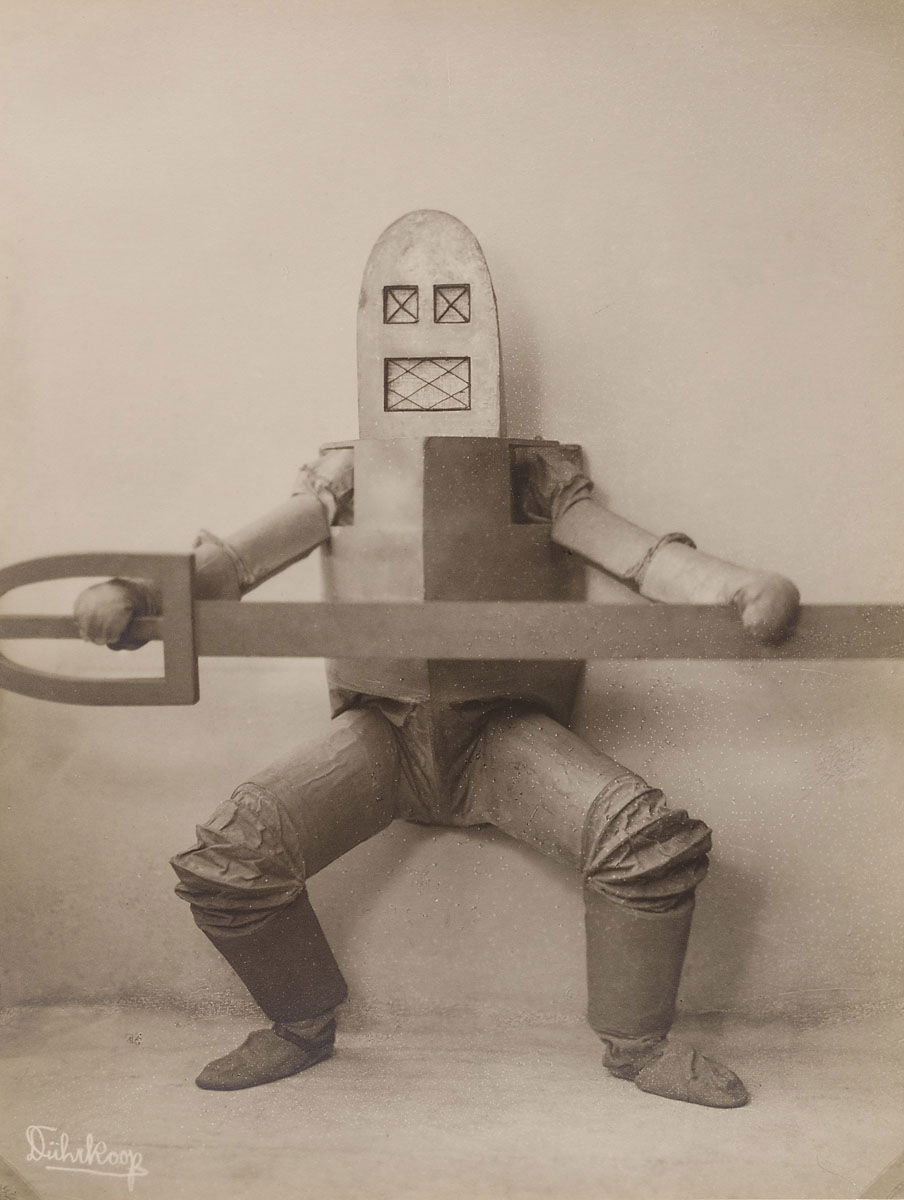

This chart shows how smaller animals with higher metabolism/faster resting heart rates generally have shorter life spans compared to larger animals with lower metabolism/slower heart rates. We humans have made ourselves an exception to this rule.

Don’t worry, you can’t decrease your actual lifespan by increasing your heart rate. It won’t fluctuate to that degree. You can only increase how long life feels.

2. Sensory Input and Focus

The intensity with which you’re focused on a subject can either speed up or slow down your internal pulses. This is why you can get really into a videogame and not notice the sun’s gone down. Or you can be totally bored in class and feel like the clock must be broken.

3. Accumulating Memories

It’s thought that the more memories we collect, the more time will seem to have passed retrospectively because you’ll have more pitstops to visit on your mental journey back through time. So what does this mean for quarantine?

Time moves slowly in quarantine if you feel you don’t have anything particularly stimulating or pleasant to focus on in the present moment. If you’re constantly shifting your focus or you’re focusing too much on wanting to be elsewhere, the pulse of your neurons firing will literally slow down and your internal clock will feel like it’s moving at a glacial pace compared to the pace on your digital or analog clock. Depressants like alcohol will slow your internal clock even further.

What’s crazy is that the time you spent being bored out of your mind will feel lightning fast in retrospect because you didn’t accumulate any significant memories. If you’ve had no novel experiences, no big life events or insights, and you didn’t find some new interest to fascinate yourself with, the good news is — you’ll look back and feel it was all a blur.

On the flip side, you can speed up your present moment, but also magically elongate your future memory of the time you spent in quarantine, by introducing multiple novel experiences, by hyper-focusing on a new topic or activity, or by changing your environment once in a while.

Why do you think so many people are suddenly shaving their heads? They’re simultaneously giving themselves something thrilling to focus on while logging a vivid memory to look back on. This shows me that, instinctively, we already know how to manipulate our own internal clocks.

Stimulants like coffee can contribute to speeding up your internal clock as well, but I’m only telling you that so you can compare it to the effects of alcohol, not as the end-all to preventing boredom. Coffee can’t make you suddenly obsessed with fun new topics like Time and Space, it can only nudge your neurons to connect a bit faster while you’re engrossed.

Now that I know all this, I have a much better understanding of what’s going on for my grandma. Her lack of motor skills forces her to focus intently on everything, so her internal clock makes her feel that time is going faster than it is. But her lack of short-term memory means she’s not accumulating things to look back on. What a confusing reality that must be. No wonder she’s always revisiting stories from her childhood. Those memories must feel so much more real than her current reality.

And what about me? What’s my excuse for being slow?

I have a space-time theory about that.

Gravity is matter’s response to loneliness. — Ellie Chu (The Half of It)

I love psychologist-backed personality tests like Myers-Briggs and The Big 5 Model, but I’ve always been a bit suspicious of them. My results always felt half-true.

“SUPER extrovert!” they’d say every time. “Go frolic with your friends! Fly, social butterfly!” Since quarantine started, everyone’s been worried about the extroverts. The New York Times has asked everyone to Check on An Extrovert Today. We’re apparently meant to be crawling out of our skin right now.

But personally? I’ve been good. Maybe it’s the relief of just being alive, but I’ve been enjoying spending my time however I want. I don’t have to deal with the pressure of constantly running around, trying to keep up with other people’s events or meetups. I can check in with my friends virtually instead. As horrific as this pandemic has been in so many ways, a massive weight has lifted off my shoulders. My social anxiety is gone.

And that all sounds pretty introverted, right? So are the personality tests wrong? I don’t think so.

In order to understand my theory, we need to delve back into some physics. Bear with me here. You ready?

…I think personality tests are Newtonian.

In Newtonian physics, space and time are considered to be independent of each other. Newton describes a 3-dimensional world where —

Space is relative.

A person on a moving train will feel just as “at rest” as someone standing on a platform. Their experience is the same but their realities are different.

Time is fixed.

Those same two people can check their respective clocks and know exactly how much time it takes to reach each other.

Einstein, on the other hand, blew everyone’s minds by describing a 4-dimensional world in which space is relative… but so is time.

Einstein was talking specifically about the speed of light and how it travels through space, but I’m referring to our internal clocks, those neural pulses we talked about, and how they can trick us into perceiving that time is moving faster or slower depending on what we decide to focus on.

I think personality tests that tell us how we interact with the world are Newtonian. Introvert vs. Extrovert, Feeling vs. Thinking, Openminded vs. Closed Off — these concepts have accounted for our unique relationship with the Arrow of Space, but not the Arrow of Time, and they certainly don’t take into account how one affects the other.

So what happens when we start thinking of ourselves 4-dimensionally?

Thought experiment!

Let’s take two different open-minded extroverts (because that’s the type of person our world seems to have been built for up until a few months ago, right?). Both relate to their spatial world the same — they love people and novel experiences. But these two interact with their world at two wildly different paces:

Extrovert #1

This person has interpreted “novel” to mean “new”. They’re a speed demon, collecting mental experiences by meeting lots of different people and having lots of different conversations.

They may enjoy collecting physical experiences as well. They want to get to the top of the mountain so they have time to climb back down and go for a swim in the lake.

If this person is focused on their tasks and enjoying themselves, time is moving quickly for them, but it will have felt slow when they look back because of all the meaningful memories they collected.

Extrovert #2

This person has interpreted “novel” to mean “noteworthy”. They’re collecting emotional experiences with the friends they already have, actively deepening those relationships.

This person may prefer a more spiritual mountain experience. They want to take note of all the colors in the bark on the trees so they have time to listen carefully to what the wind is telling them.

This person may seem sluggish in comparison to Extrovert #1 but if they’re focused on their tasks and enjoying themselves, they will also experience time as moving quickly. And it will also have felt slow when they look back because of all the meaningful memories they collected.

You show me continents, I see the islands, You count the centuries, I blink my eyes. — Bjork

“Introversion/Extroversion” and “Level of Openness” aren’t synonymous, by the way, I just put them together here for my own purposes.

These same principles work for introverts too, they just don’t feel that gravitational tug to be close to people as strongly. Their mental tasks may be solo tasks and their emotional tasks may be more internal.

People who aren’t “open-minded” and don’t enjoy novel experiences may prefer the retrospective blur, which is fine.

Dang, will you get a load of that sweet, sweet symmetry?

I fought angrily against seeing particular types of poetic organization because it seemed awful to see my own life and these actual events in that way. But when you put forth an intention into the universe to speak a certain truth and narrate a certain period of your life, you start to see the sorts of symmetries that you are not usually supposed to be able to see until you are on your deathbed and your life flashes before your eyes. And you see exactly why everything happened. And even the most painful things you’ve ever been through can seem unbearably beautiful. — Joanna Newsom

Before this pandemic forced us all to slam on our brakes, my patience with myself had reached a breaking point. I was Extrovert #2 trying to live in an Extrovert #1 world.

This article took me two weeks to write because I delved into something that I used to think was beyond my grasp or level of interest, and that’s a big deal. Every mind-bending revelation, every “aha!” moment, every breathless, metaphysical conversation with someone has felt like a new evolution of self. I don’t want to give that up.

I like my pace.

This pandemic has irreversibly shifted our trajectory through space and time. If anything good comes of this particular entropic increase, I hope it’s that we feel freer to question where it was we thought we were going in the first place. A lot of our anxiety comes from feeling like we don’t quite fit the paradigms that we’d collectively agreed upon as a society. This is a hell of an opportunity to change those paradigms.

A lot of people are using this moment to seriously consider fundamental shifts in how we interact with space and time. Shifts like the 4-day work week, universal basic income, education reform, sustainable farming, and circular economies. Because, as comfortable as a select few people are to stick to the old systems, a majority of us are uncomfortable.

Which means the probability of change is in our favor.

Comments